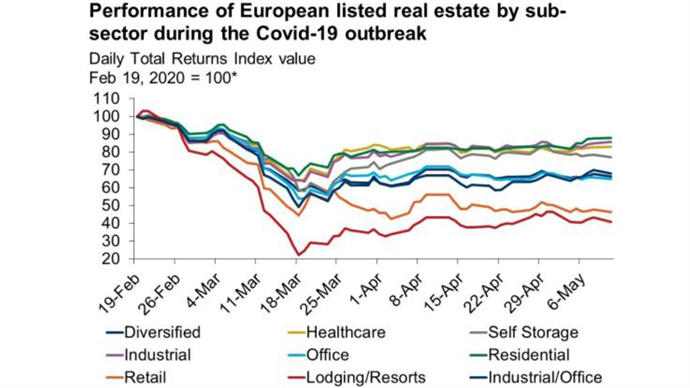

Economic turmoil is putting a premium on LTVs and solvency, while making the case for Europe’s shareholders to get active, like in the US.

MAGAZINE: Covid-19 reminds listed sector of financial fundamentals

- In Magazine highlights

- 09:07, 04 September 2020

Premium subscriber content – please log in to read more or take a free trial.

Events

Latest news

Best read stories

-

Investis expands Swiss resi portfolio with €149m acquisition

- 20-Dec-2024

Swiss real estate group Investis has boosted its real estate holdings with the CHF 139 mln (€149 mln) purchase of prime residential properties in Vaud canton.

-

- 20-Dec-2024

Deka snaps up Paris office building for €89m

-

-

- 23-Dec-2024

Indurent gets green light for Staffordshire shed

-

- 23-Dec-2024

NBIM snaps up 80% stake in Trinity office tower